This is a talk I gave at Webstock in June 2019. A text version and the slides appear below.

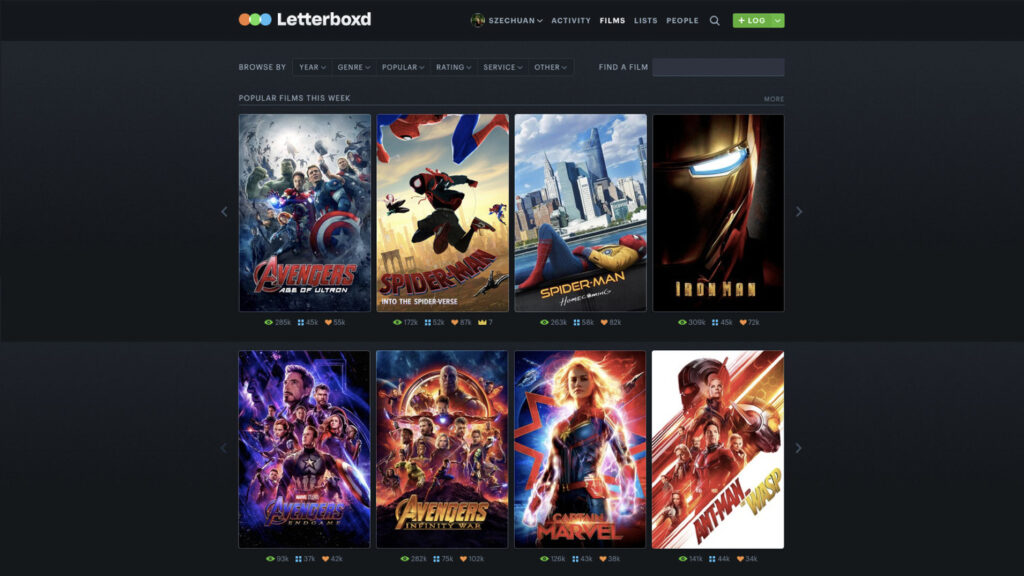

Last year, I went to see a little movie called Avengers: Infinity War.

I saw it at the Alamo Drafthouse in San Francisco, which is an independent cinema that cuts its own pre-roll clips.

Before they screened Infinity War, they showed a pre-roll clip of two comic boy guys sitting in their store.

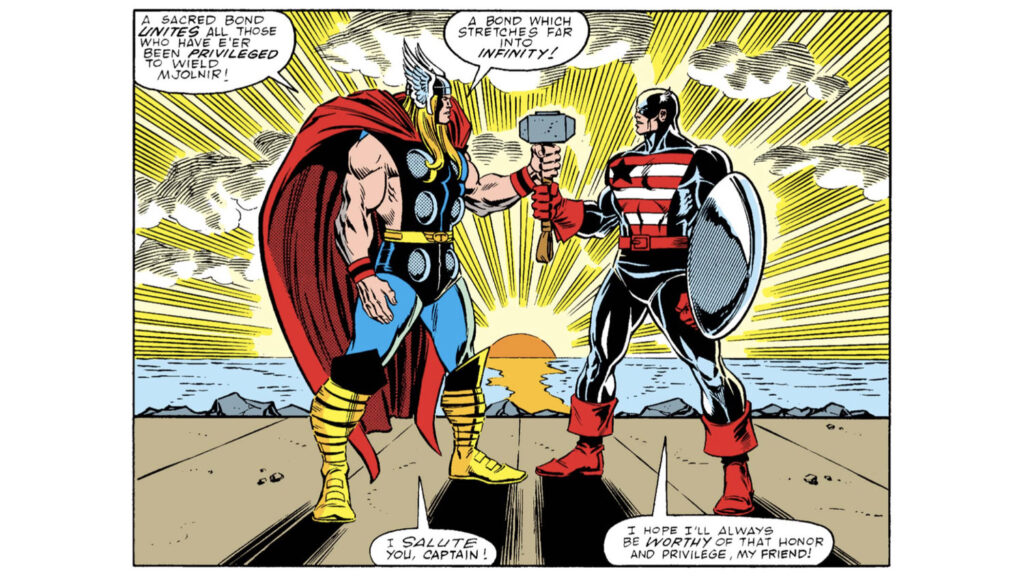

They were discussing their favourite issues of Avengers comic books over the years and their favourite storylines including Captain America, and Thor…

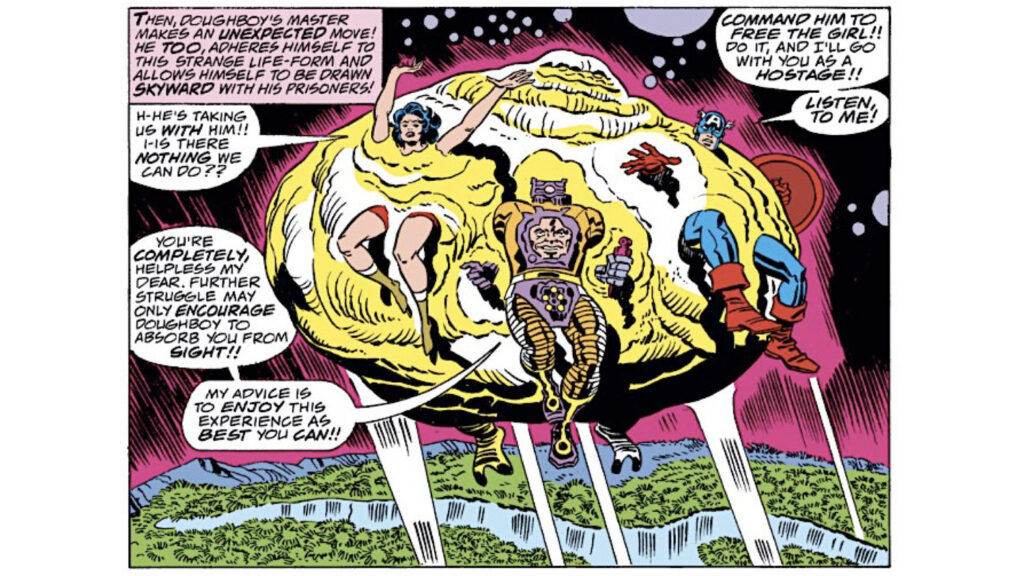

…and even that slightly lesser known Marvel character, Doughboy.

I realised, as I sat there, that Infinity War was not exactly a movie for beginners. After twenty odd Marvel movies, it encompassed over thirty characters and storylines. It was the culmination of a decade of film-making.

On its face, it was a movie specifically designed for the Comic Book Guys.

And yet, there I was with one of my best girlfriends, having never once opened a Marvel comic, and still excited as all hell.

So, what was I doing there?

It’s hard to imagine now, living in a time before all movies were basically Marvel movies.

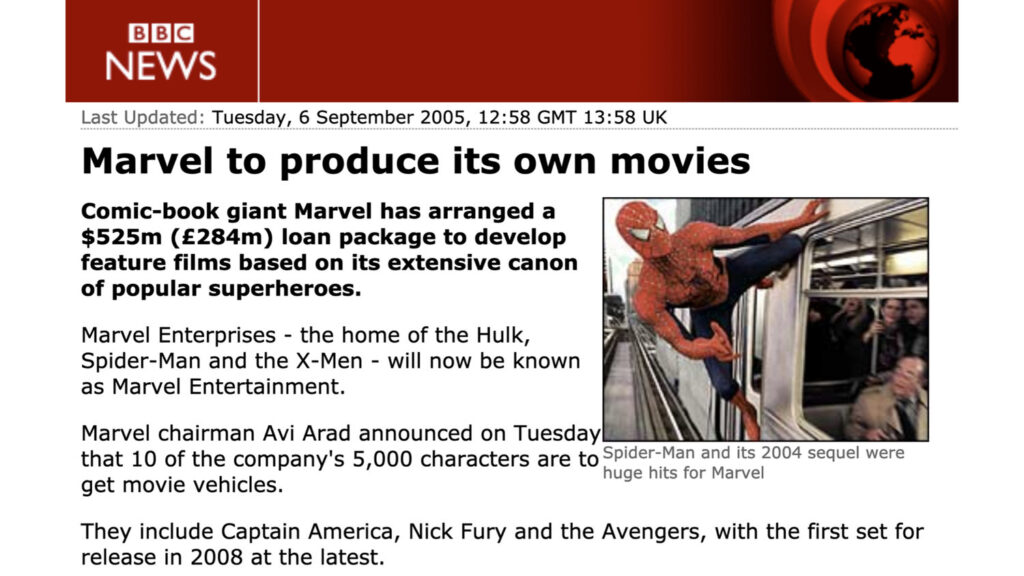

But Marvel Studios started out in the 90s as a licensing company. It sold the rights to Marvel characters to other studios, who turned them into movies. Marvel as a group were in financial dire straits and filed for bankruptcy in the mid-nineties.

After a massive restructuring, Marvel decided to take some of the characters it had left, and try to self-finance its own films, so that it could keep all of the revenue. Armed with a $525m loan, it announced a ten-property series in 2005.

It was an enormous creative gamble. While comic book characters had always existed in a continuous world, where they moved in and out of each other’s storylines, movie characters did not. They had prequels and sequels, sure. You could do a Superman 1, 2 and 3. But not a shared universe comprising completely different movies and characters.

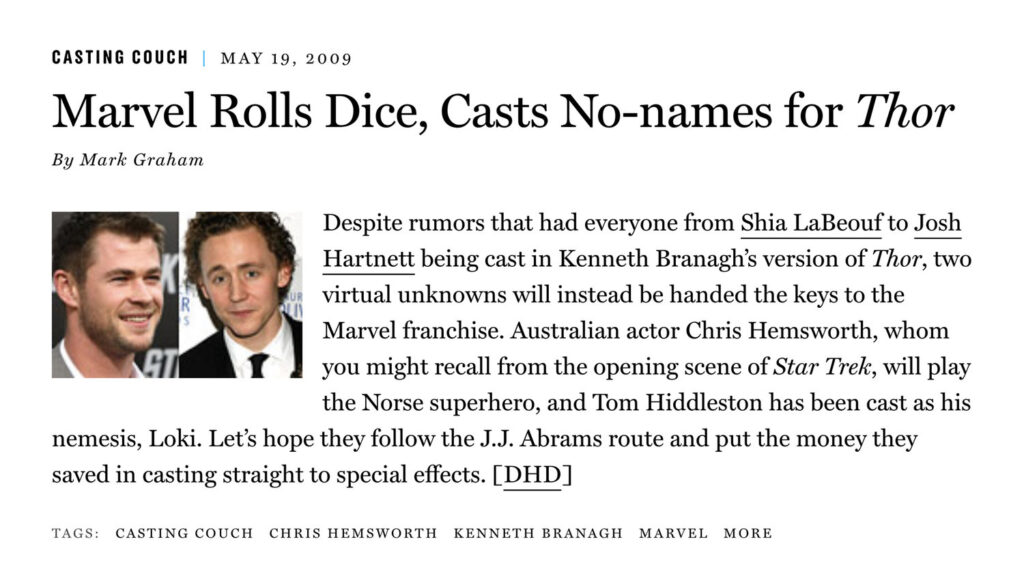

And basically, other than the Comic Book Guys, no-one had heard of these lesser known superheroes like Doctor Strange.

And even fewer people had heard of the proposed cast.

And yet here we are – 22 movies and 20 billion dollars at the Box Office later.

Like so many things in my life, I came to the Marvel Cinematic Universe, or MCU to its friends, through online fandom.

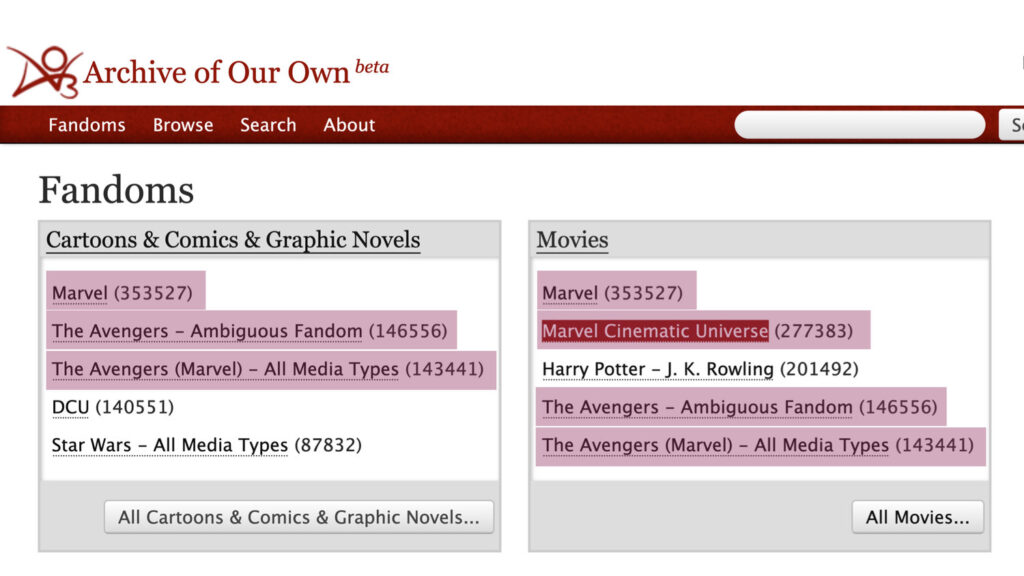

Over the last few years, I started to see more and more incredible fan work being created around the MCU.

Hundreds of thousands of stories being written.

Absolutely gorgeous digital art.

(credit: Sophia Canning)

(credit: Aliya Chen)

(credit: zazrichor)

(credit: Hazel Gee)

(credit: Takumi)

This kind of fandom is called “transformative” fandom. It takes the original source material and adds to it, breaks and remakes it. Transforms it. Depicts the characters in new situations, imagines “what if?”

There’s something generative about transformative fandom. Something that’s about ideas and possibilities.

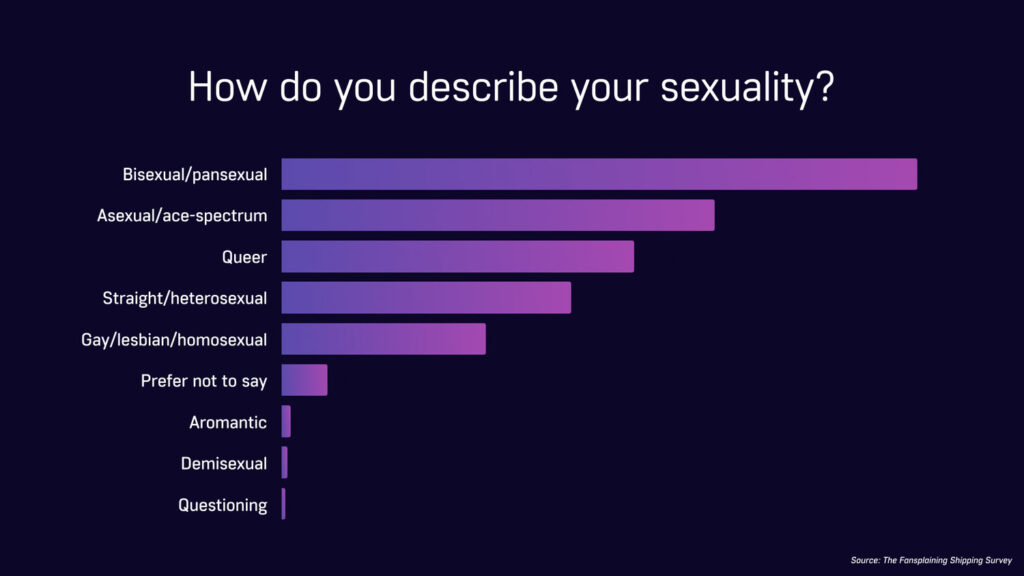

And, generalising, it tends to be female fans and queer fans that are more inclined to engage in this kind of fandom. These are the demographic results of the recent survey conducted by the Fansplaining podcast, which had over 17k responses.

In part, this is because it lets fans create the representation that they don’t see on the page and on the screen. A way of telling their own stories, or versions of the stories, in which they can see themselves.

As Henry Jenkins said, way back in 1997, “If you go back in history, the key stories we told ourselves were stories that were important to everyone and belonged to everyone. Fanfiction is a way of the culture repairing the damage done in a system where contemporary myths are owned by corporations instead of owned by the folk.”

Transformative fandom tells the stories that exist in the cracks.

“A text can contain more than the sum of its words, that a whole other story—a whole other world—may exist in the cracks and spaces between sentences, accessible to any reader paying the right kind of attention. It’s a form of magic.”

And sometimes, transformative fandom exists just because it’s fun.

(credit: @McJesse)

We’ve been on a journey with transformative fandom. At first, authors and publishers and studios weren’t sure how they felt about all of this. There was a lot of push back. Attempts to stop this kind of work as infringing copyright and so on.

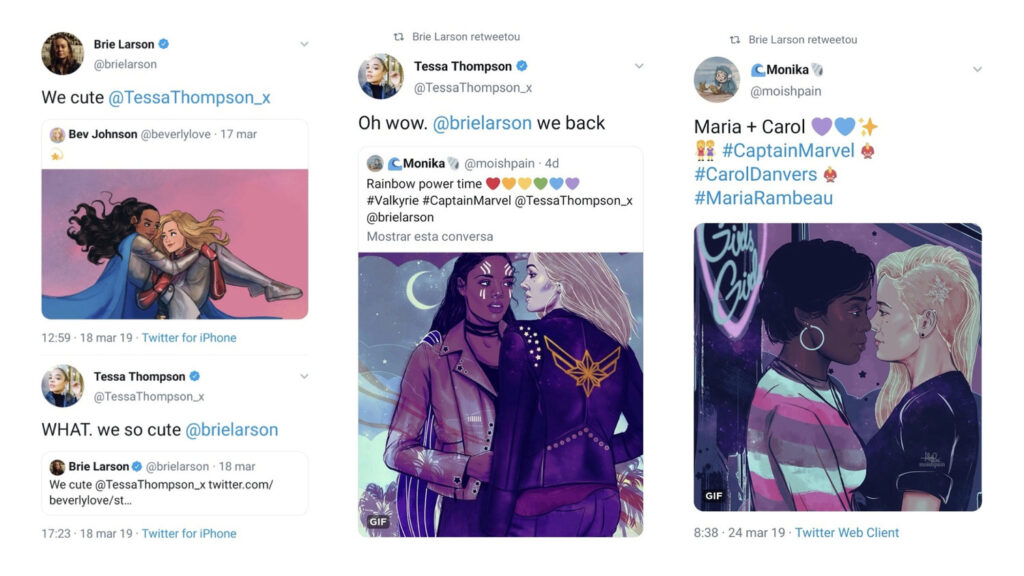

But now we’re here, a world in which the two actors playing characters in these movies are openly sharing and celebrating fan art on social media that depicts them in relationships never seen on screen.

When we think about fandom, we can categorise it broadly (I’m generalising wildly, but go with me for a moment) into two different kinds – this transformative kind. And then…

The other, more traditional kind of fandom, is what we call curatorial fandom. This is what one of my friends referred to recently as “anorak” fandom, which is very British way of describing it. It celebrates the fans who know the most facts, who are the most expert about the canon. Sports fans are great examples of curatorial fans – where you’re prized for knowing player statistics and starting line-ups. Star Wars fans, who can tell you all about the extended universe and which bits contradict what. Marvel fans who can explain to you how an arc reactor works, or…

… or who the strongest Avenger is.

Generalising, curatorial fans tend to be men.

Of course, in an ideal world, all of this glorious fannish activity would co-exist happily.

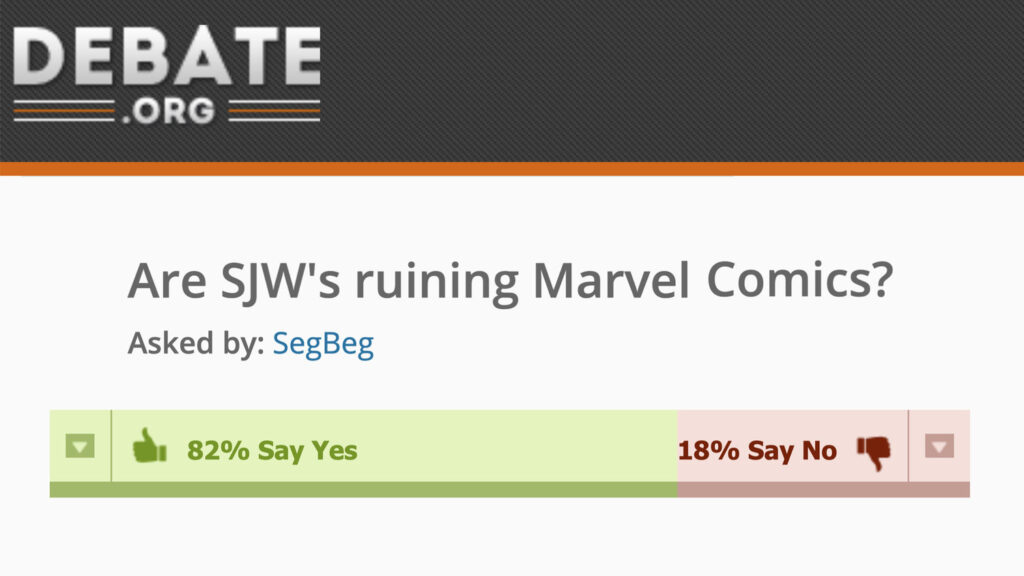

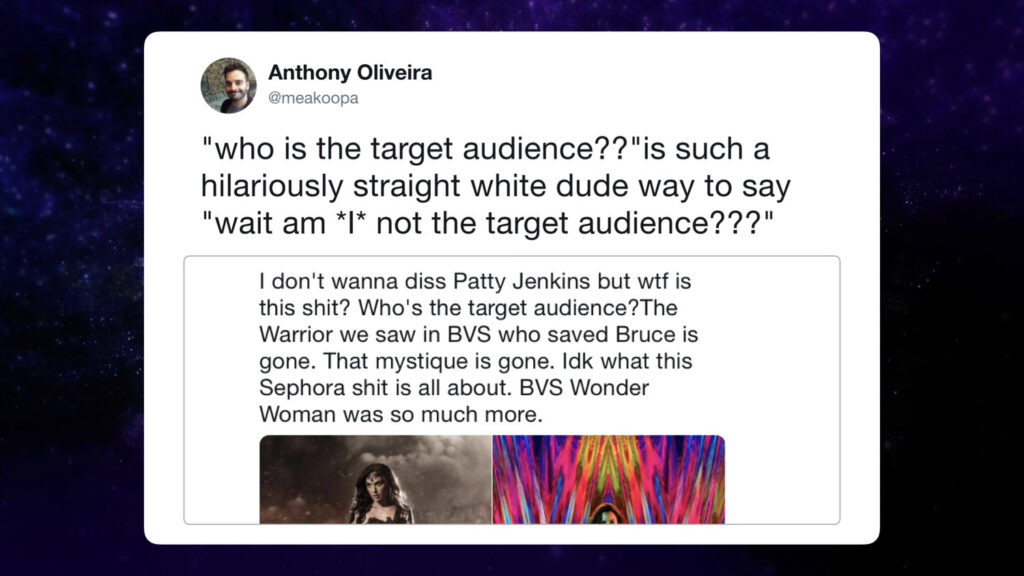

Unfortunately, for some fans, the Marvel Cinematic Universe is descending into chaos and it’s got nothing to do with Thanos. For the uninitiated among you, SJW stands for “social justice warriors” a label slapped on pretty much anyone interested in progressive ideas.

So, what’s going on?

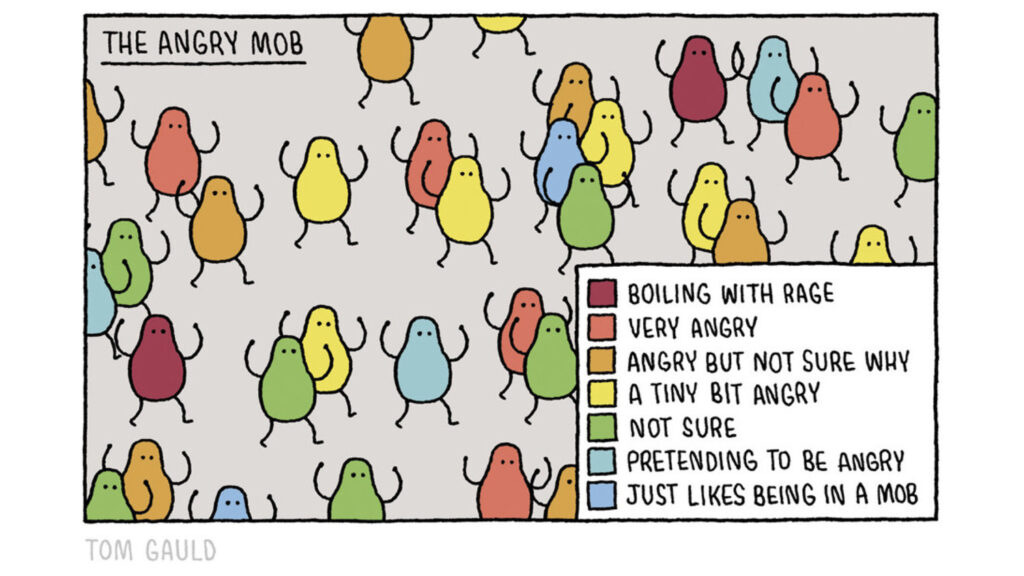

We get the backlash whenever we get new bits of canon: new Star Wars movies, a new Ghostbusters.

The backlash comes from curatorial fans. They don’t like the idea that canon is changing, or that the things they’ve learned and know to be true are changing.

Remember, in their framework, being a “Good Fan” means knowing all the things. If you’re changing the canon, you’re undermining that and need to be stopped.

Then you have to add in that popular culture is also changing (not as fast as we’d like) and so we’re getting more diverse casts, the inclusion of characters of colour and queer characters. We’re seeing a tiny bit less of the straight white man. And there’s a perception that these changes are “ruining” the stories that curatorial fans love, because they’re used to seeing themselves on screen.

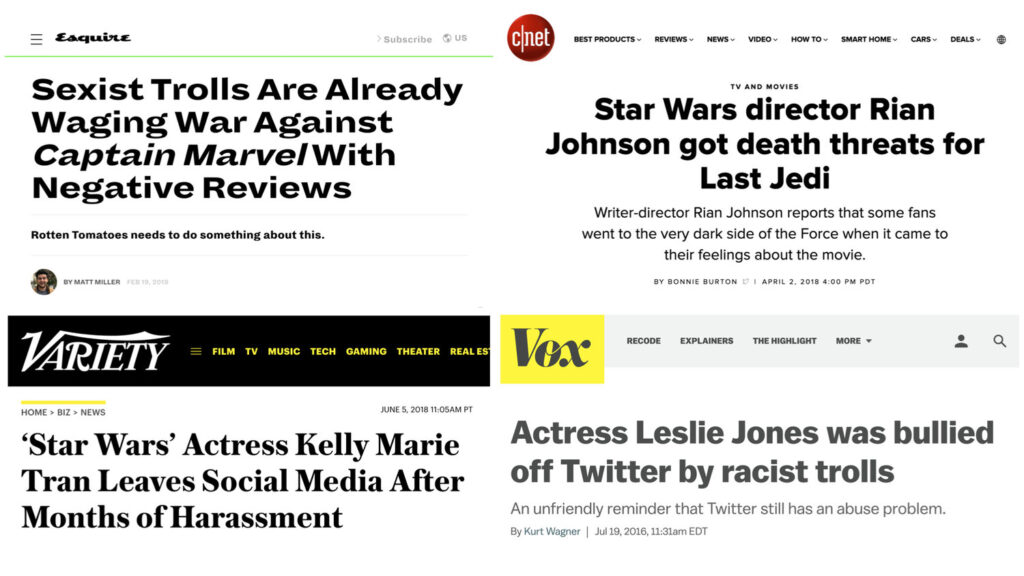

So they lash out at these actors, and at the directors and creators.

Now – I want to make an important and giant qualifier here. I am not suggesting that transformative fans are flawless, or that there aren’t significant problems in transformative fandom, particularly with racism. Transformative fandom is overwhelmingly white, and that can lead to ugly behaviour, and I’m going to talk about that more in a minute. Transformative fans deeply invested in the relationships they support can be just as awful to tv showrunners and actors when the show doesn’t take the direction they want. There are angels and demons on both sides of this divide.

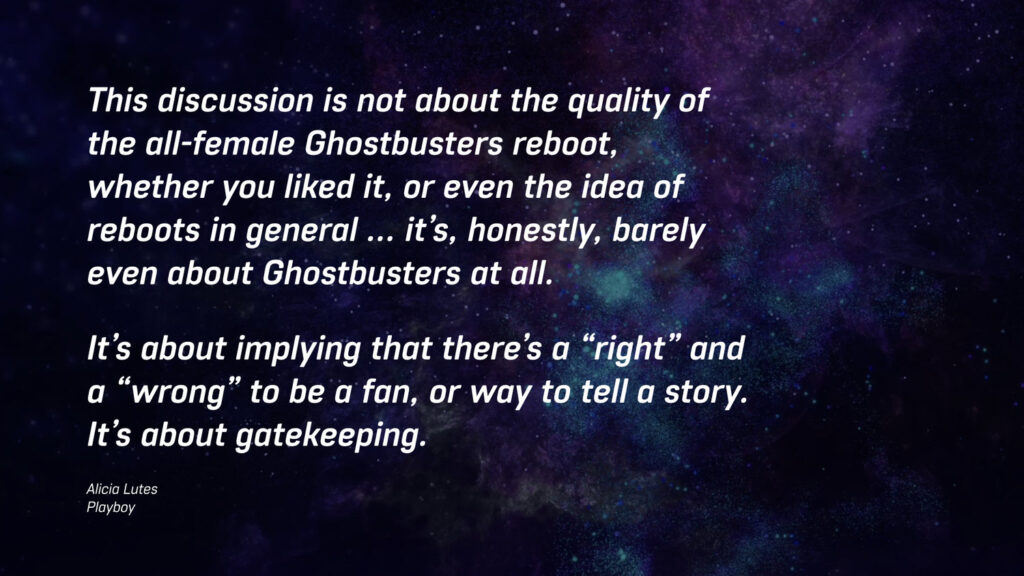

But what we’re seeing with these angry curatorial fans is a kind of gatekeeping. The idea that there’s a right way and a wrong way to appreciate these stories.

Let’s look at a recent example.

Recently it was announced that Jason Reitman would be directing a new back-to-being all male version of Ghostbusters. And the public reaction online from curatorial fans looked a lot like this. “Keep the feminist bull out of it. Don’t make women the “point” of the story.”

And Reitman totally validated this, by saying:

“We are, in every way, trying to go back to the original technique and hand the movie back to the fans,” “I love this franchise. I grew up watching it; I consider myself the first Ghostbusters fan… I want to make a movie for my fellow Ghostbusters fans.”

Here’s the question. Who are your fellow Ghostbusters fans? Who are you taking it from to hand it back??

As Alicia Lutes wrote, “This discussion is not about the quality of the all-female Ghostbusters reboot, whether you liked it, or even the idea of reboots in general … it’s, honestly, barely even about Ghostbusters at all. It’s about implying that there’s a “right” and a “wrong” to be a fan, or way to tell a story. It’s about gatekeeping”

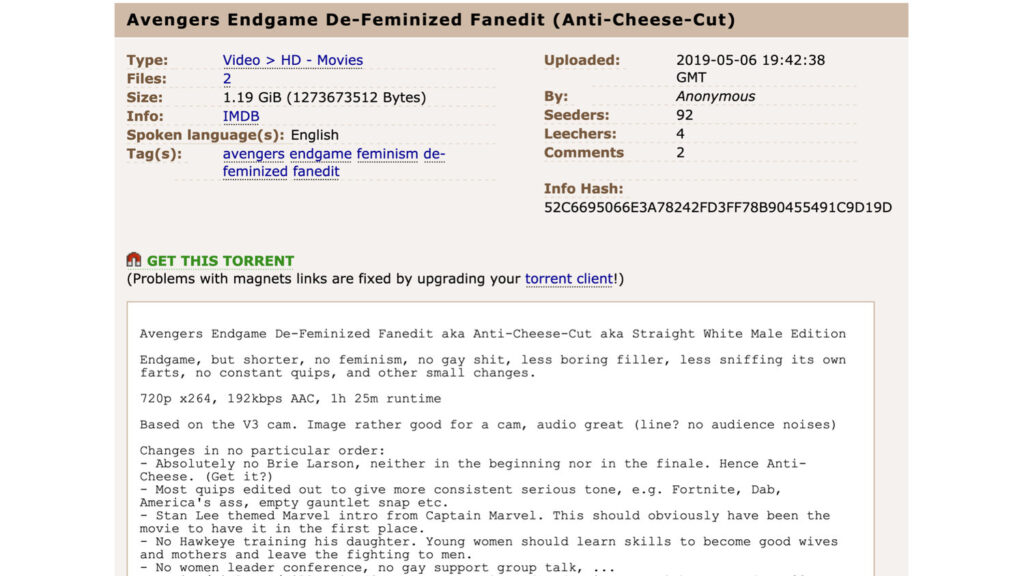

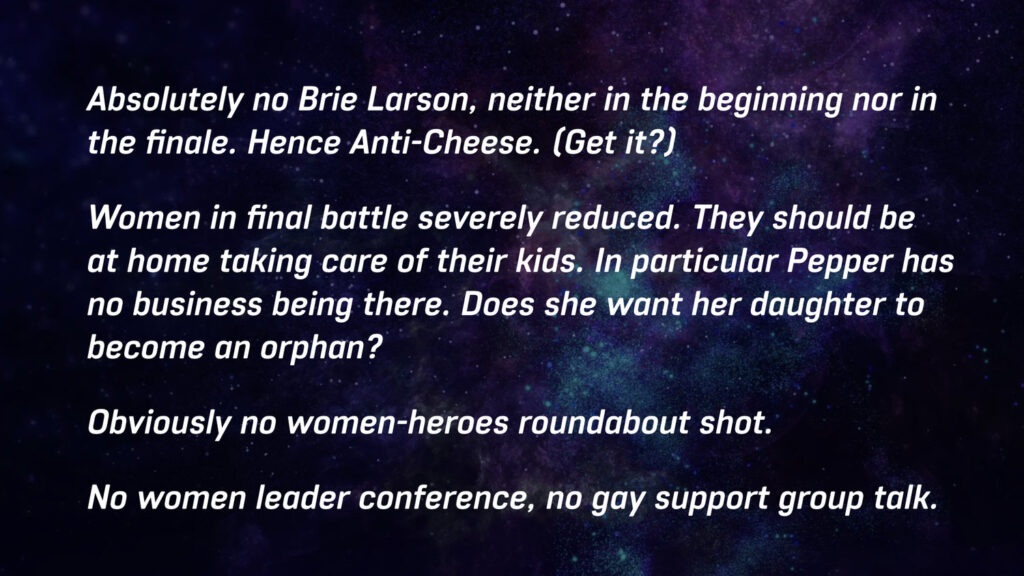

At its most preposterous, this attitude leads some “true” fans to cut versions of The Last Jedi and Endgame that remove all of the troubling social justice content.

This version of Endgame weighs in at a lean 1 hour 25 minutes, half the length of the actual movie, and apparently contains no Brie Larson. No women at all, actually. And definitely no gay support group.

So now Marvel is the latest franchise to be under the gun.

First the blatantly racist criticism of Black Panther.

And then Captain Marvel stepped into the firing line.

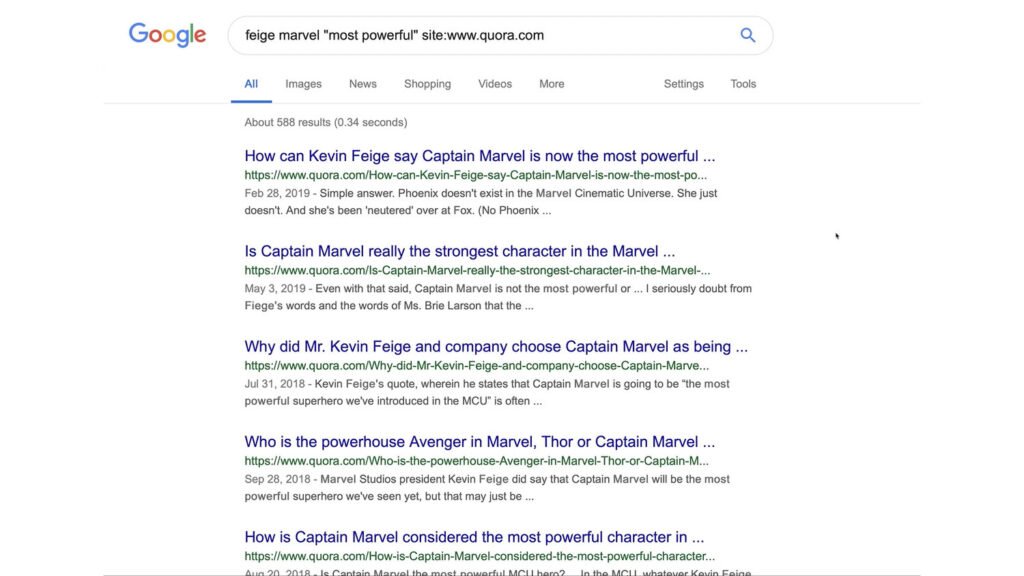

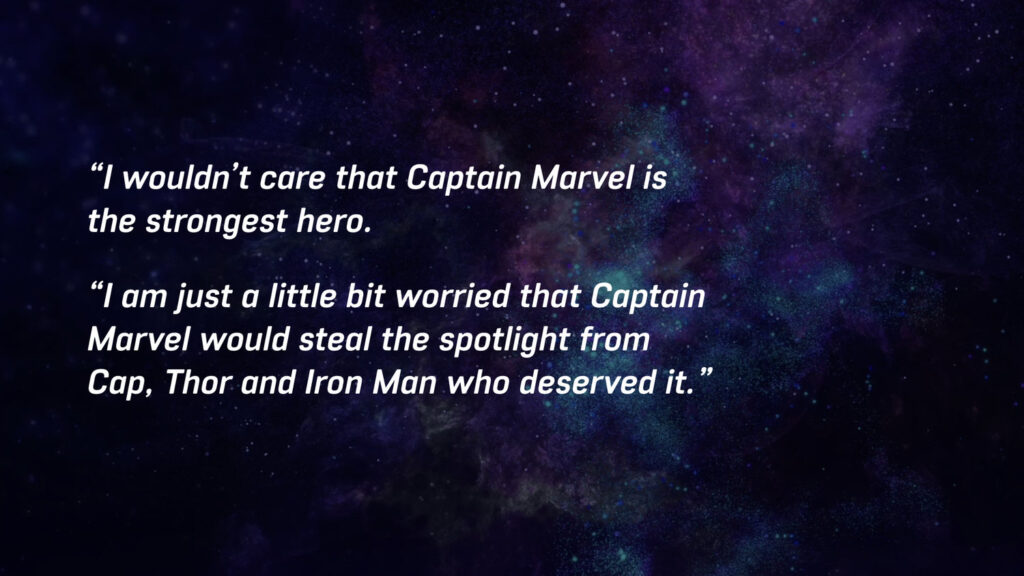

Producer Kevin Feige announced that Captain Marvel would be the most powerful hero the MCU had yet seen. And let’s say the curatorial fans were not best pleased.

Many fans were outraged that he’d announce something like this “without providing evidence.”

Many were furious because “It’s not because its accurate to the comics.”

And still others felt that it was deeply unfair to the existing characters Cap, Thor and Iron Man who deserved the spotlight.

Brie Larson, the actor playing Captain Marvel, fueled their anger, taking an active role in inviting interviewers on the press junket who were not just white men,

And speaking actively about the need for queer representation in the MCU.

And you can imagine how that went down.

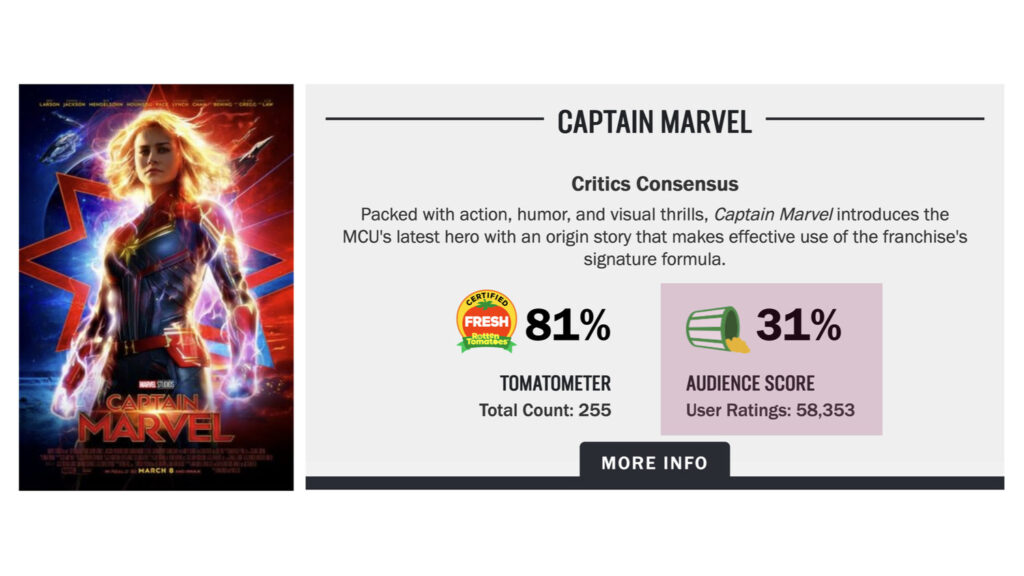

Curatorial fans downvoted Captain Marvel so aggressively ahead of its premiere that Rotten Tomatoes had to disable its pre-release voting mechanism.

Here’s the interesting thing, though. Of course these fans are wrong.

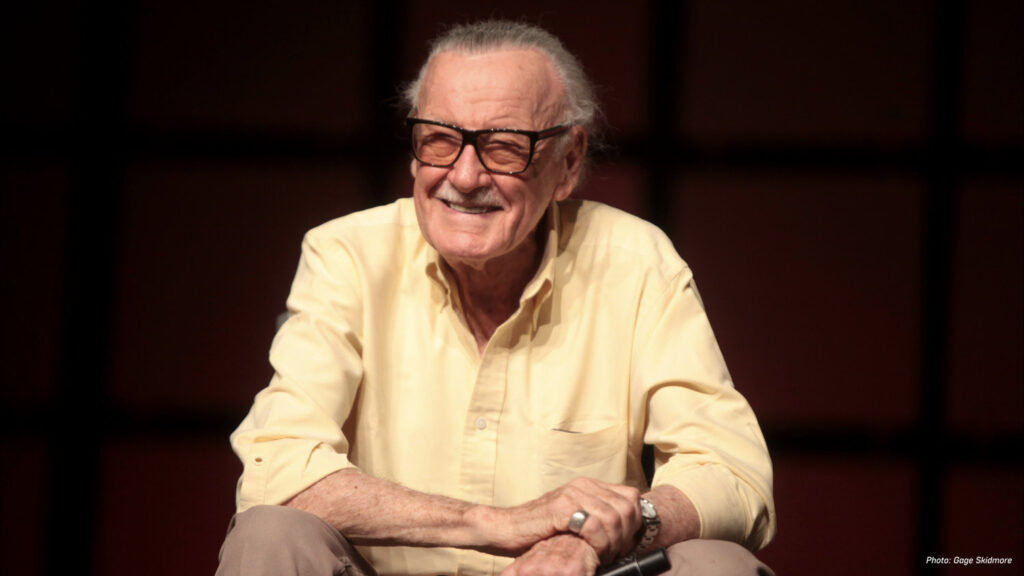

Stan Lee the iconic creator of some of Marvel’s most beloved characters was speaking openly against racism and anti-semitism way back in the 60s

He said: “Bigotry and racism are among the deadliest social ills plaguing the world today. But, unlike a team of costumed super-villains, they can’t be halted with a punch in the snoot, or a zap from a ray gun. The only way to destroy them is to expose them — to reveal them for the insidious evils they really are.”

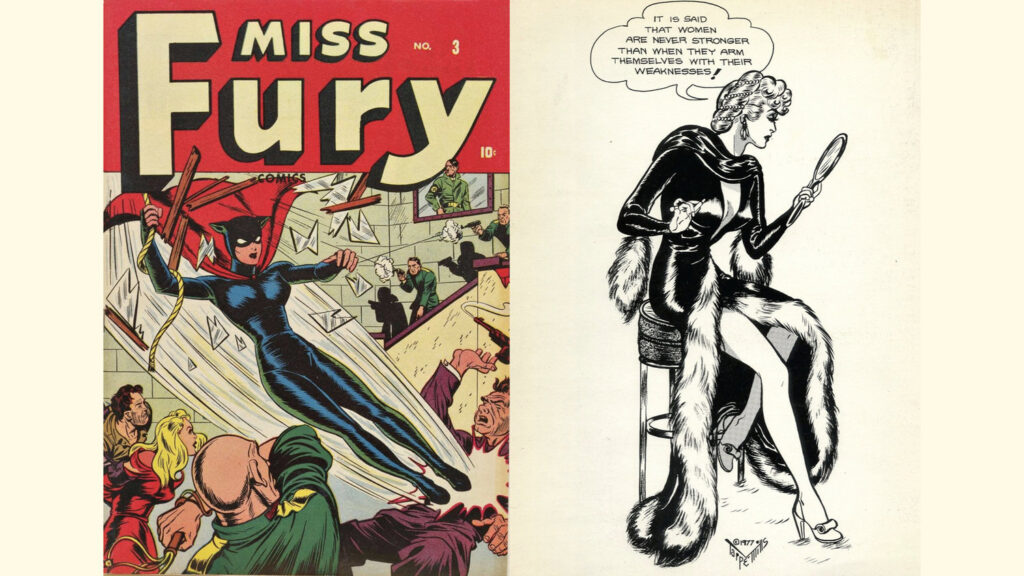

Even before that, in the Golden Age of comics, a woman was the creator and writer of Miss Fury. Miss Fury could fly a fighter plane when she had to, jumping out in a parachute dressed in a red satin ball gown and matching shoes. She was also a crack shot. Half way through the series, Marla got a job, and – astonishingly, for a Sunday comic – became a single mother.

Over the decades, Jane Foster has taken a turn as Thor.

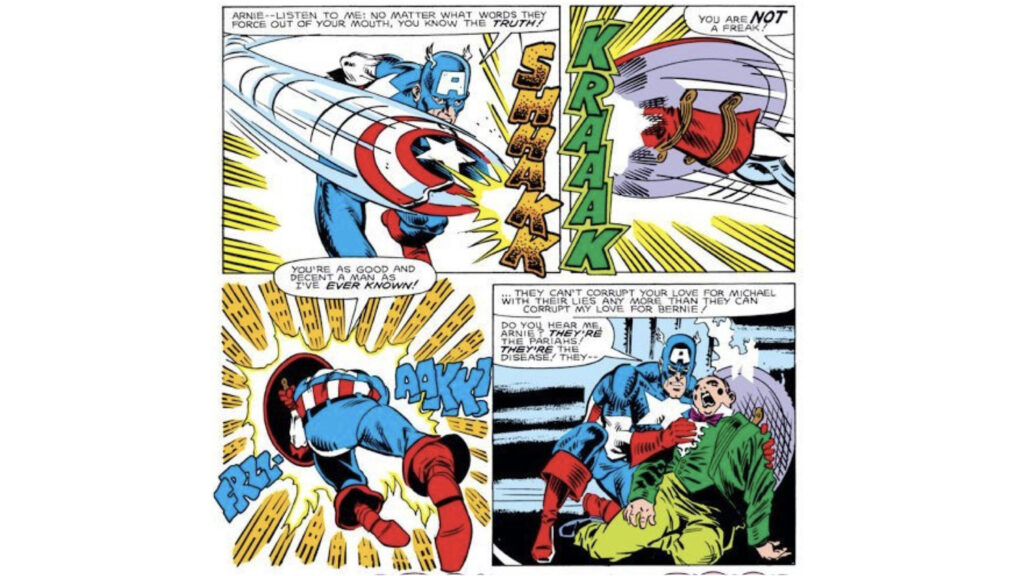

Captain America’s best friend has been gay for over thirty years.

Ms Marvel, the comic book about a female muslim superhero, topped the New York Times bestseller list.