This is a talk I gave at Microsoft’s TechEd in Auckland in 2014. Full audio of the talk with the slides is beneath the text below.

Why sharks? Because sharks are eating the internet. Literally. Last month Google released photos of a shark snacking on one of its trans-Pacific fibre cables, and now they are wrapping them in kevlar to try and keep the sharks at bay. The best theory so far is apparently that electric impulses coming from the cables are mimicking the sharks’ prey. The better answer is that sharks are eating the internet.

As a partner at a law firm, and over the last five years, I’ve worked with over 100 tech startups, including companies that have grown to be extremely successful.

Today, in the best tradition of a Buzzfeed listicle, I’m going to distil everything I’ve learned down into ten things you should know, to set your startup dream on the path to success, and under each of these I’m going to try and give you a tool, or a simple way, to tackle these sharks.

So let’s start at the start. You’ve got a great idea for an app that’s going to change the world. You’ve got some people you want to work on it with, and everyone is convinced that the project’s going to be a success.

Here’s where kiwi founders often make their first mistake, and it’s a significant one.

We’re a pretty egalitarian culture. Or possibly we are too reticent to have really hard conversations with people, even people we’re going into business with. And for our startups, this takes the form of splitting the shares equally between founders.

You know why that happens? Because nobody wants to be the person saying, “If this idea succeeds, I deserve more of it than you do.”

But it’s critical. It’s the first important decision a company has to make, and making the wrong one quite literally takes money off the table. US academic research shows that founder teams who opt for the equal split suffer on average a 10% discount on the company’s pre-money valuation going in to the first financing round. Why is this? There are no clear indicators. But what the researchers believe it points to is that the founder teams who are prepared to have the hard conversation at the start about respective contributions.

NZ founders need to bust out of our too-polite mindset and have a proper conversation about who is doing what, what it’s worth to the business, and what happens if it doesn’t work out.

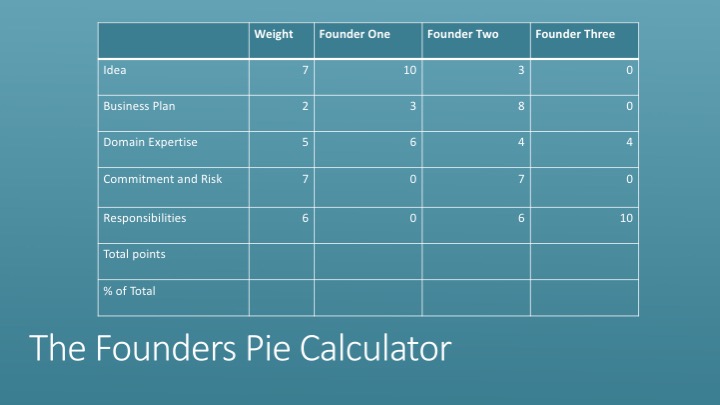

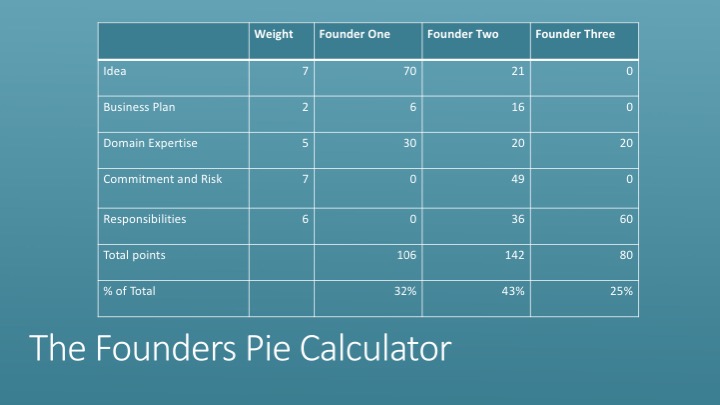

Here’s one simple way to attack it. It’s called the Founders Pie Calculator, and it was designed by a US academic, Frank Demmler.

Basically, the idea is that you take any startup business, and you say there are these five components to it.

1 – there’s the idea. All great start-ups begin with the great idea, so it’s got to be worth something. But equally, ideas are worthless unless they’re executed on properly

2 – there’s the business plan. How is this thing going to make us actual money, how are we going to pitch it to investors, there can be a lot of work in that.

3 – domain expertise. Does anyone on the team know this market, bring unique skills or understanding or contacts?

4 – commitment and risk – Frank likes the old saying that a “chicken is involved in breakfast, but the pig is committed.” Who is chucking in their job and working at this full-time? Who is staying on the sidelines?

5 – responsibilities – where does the buck stop. Who is building the thing?

Now, in each business, the relative weight of these components is going to vary. So, for example, if you’ve looked at a very successful business overseas, say an online marketplace for selling secondhand goods, or a daily deal site, and you think, “huh, I could build that in NZ”, then your weighting for the “idea” might be pretty low.

Conversely, if you’ve come up with a way to provide instant accurate medical diagnosis via a smartphone, then the weighting on the idea is going to be much higher.

So, in this first column, give each a weight out of ten.

Then for each member of your team, work out how much they bring to the table in each of the areas. Again, this isn’t rigorous science, but you’ll be amazed at what this conversation forces you to confront. “What do you mean my rolodeck full of contacts doesn’t merit me a TEN?!”

Then it’s just a question of maths. Out the bottom pops a suggested equity split. And you’ll note, it doesn’t suggest they get 25% each.

This is a tool for GUIDANCE only. No one should hang their hat on it, but it’s really useful framework for entrepreneurs to start valuing their contributions properly at the outset. It will make your more confident in starting those discussions.

Here’s the next thing to do at the start while you’re all still friends. Resolve the conflicts before they happen. How? by writing something down. Pretty much anything you write down is better than nothing at all.

If you’ve set up a company, and you have shares in that company, at a bare minimum you need a shareholders’ agreement.

At the outset of a new venture, everybody involved is excited about the project, positive about its future prospects, and in agreement on most things. It’s hard to imagine a time when you might not feel the same way.

But things change. One of the founders gets a great job opportunity to move to another country, or wants to take time out to start a family. One of you wants to expand into Australia, but the others think it’s a terrible idea. You get approached by someone who wants to buy the business, but only some of you want to sell.

If you haven’t agreed anything in advance, you may find yourself in an incredibly stressful situation, facing disagreement without any framework to help you deal with these issues.

Sit down together as a team and dream up all of your best and worst outcomes. And record what you want to have happen.

A good, simple shareholders’ agreement should deal with:

– decision-making

– selling shares

– bringing on new shareholders

– defaults and disputes

That all sounds a bit serious? Doesn’t need to be. Even a record of emails will help down the track.

And if you haven’t decided yet whether what you’re working on is going to be a business. Maybe you’re just collaborating on something in your weekends, banging around some ideas?? Still. This is almost worse.

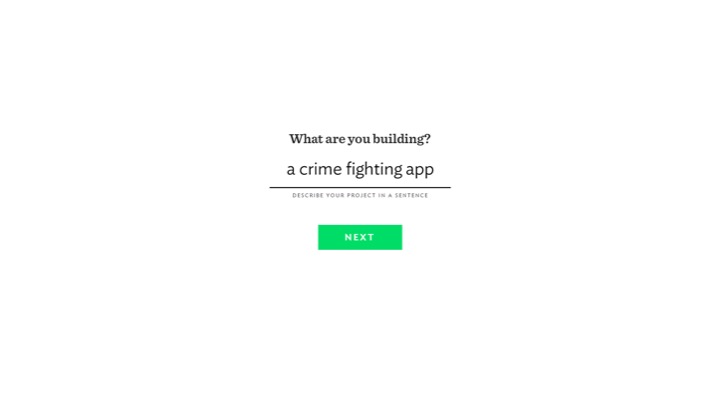

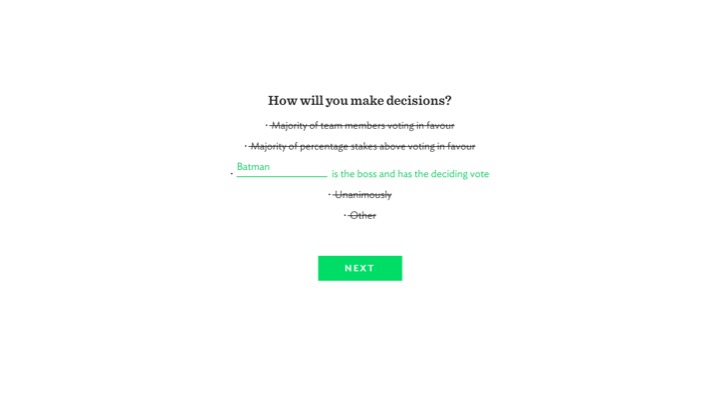

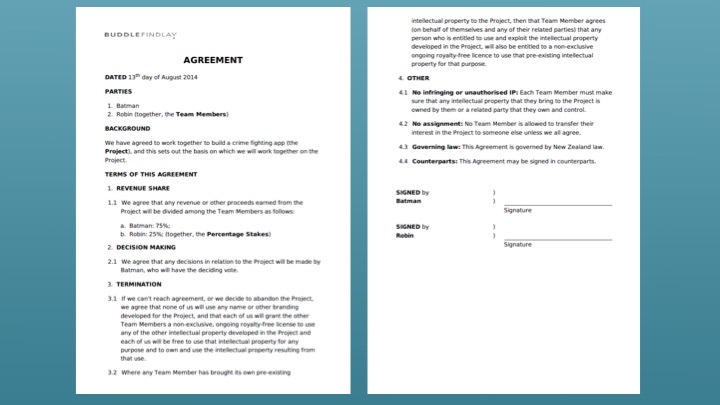

Why? While you work together with someone on a project, you’re creating joint rights in that project. And if you fall out or decide to go your separate ways, there can be some really terrible outcomes. Here’s something I came up with that can help. This tool will ask you five very simple questions about your collaboration.

First, who are the members of your team.

Second, what is it that you’re building.

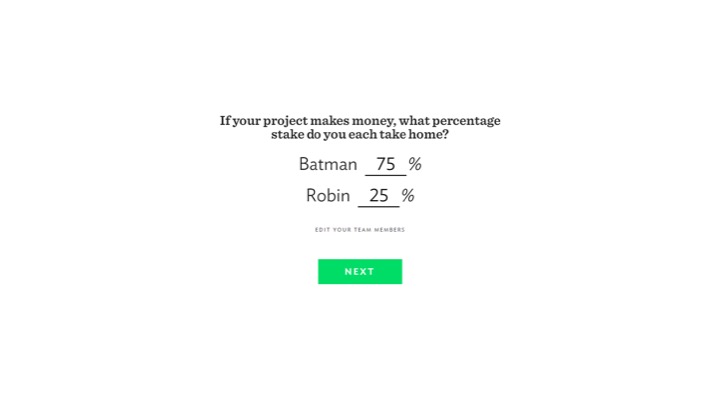

Third, if the project makes money, what percentage do each of you take home. Note, this might mean revenue, or it might mean if you sell the project or idea to someone else.

Four, how will you make decisions. This might be by majority, or it might reflect your percentage shares, or you can pick some other method. I’ve seen at least one that says “knife fight”.

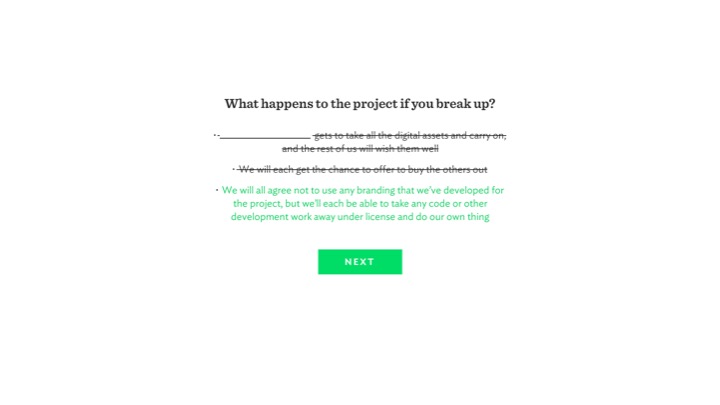

And finally, what happens to the project if you break up. You can decide that one of you gets to take the digital assets and carry on. You can have the chance to buy one another out. Or you can fork the project at that point, abandon the branding, take the code and walk away.

And that’s it! You can do this on your phone, in a bar, as soon as you come up with the idea. And then you just hit the download button.

Like MAGIC you’ll get a simple, two page agreement, converted to all the appropriate legalese, and you can just sign it and stick it in your dropbox and hopefully never think about it again.

Intellectual property is confusing, particularly in the technology sector. Daunting terminology around trade marks and patents, coupled with overseas examples of accusations of infringement, ‘patent trolling’, and aggressive cease and desists, have made the whole area seem difficult and scary for new entrepreneurs.

You can either just bury your head in the sand, or alternatively there are a number of practical steps you can take to lay a good foundation for protecting your intellectual property right from the start.

First, think seriously about the name of your company, product or service. The spate of dropped vowels that characterised Web 2.0 businesses like Flickr and Tumblr served a valuable purpose in this context as an invented word is the easiest to protect. If a word doesn’t exist yet, you reduce the risk that you’re infringing on someone else’s rights, and you’re less likely to run into difficulties with trade mark registrations on the basis that your name is too ‘descriptive’.

Even if you choose not to get creative with the English language, at a minimum you should search as extensively as you can online to see if your name is already in use either here or overseas, or if other companies in your industry are already using similar names or logos.

Finally, make sure the company owns everything that you think it does. Often in the early stages the founders will be doing a lot of the development work themselves, but you might also pay other people to assist, get friends to help out, or even promise ‘sweat equity’ to others who might join the team in the future. Without oversimplifying matters, unless the company is paying someone to do the work and/or you have a clear agreement, the intellectual property in the work will ordinarily belong to the person creating it. Things can get more complicated if members of your team are working on this project after hours while they are in full-time employment. Often the starting point of an employment agreement is that anything you create belongs to your employer, even if you’re only working on it in the evenings or on the weekends. The last thing you want is to have the ownership of your code, or your product, become unclear.

You can minimise this risk by making sure everyone who is working on the idea has an employment contract or contract for services with the company, clearly setting out what they will be doing, and stating that all the intellectual property and improvements created belong to the company.

Where software is involved, make sure you have licenses for all of your source code. This is particularly true where you use open source code. Understand what you’re using, and what your obligations are. Keep good records.

The golden rule should always be to make sure that what’s built for the company is owned by the company, and that this ownership is clear and uncontested. This might not seem important on day one, but next we’ll look at what it means to be ‘investment ready’, and why this matters whether or not outside investment is on your horizon.

We’re victims at the moment of a particular narrative that says “success” looks like Mark Zuckerberg. This week a report came out of the States showing that there are now 25 mobile internet companies with valuations of $1b or more. Companies like Uber, Whatsapp, Dropbox and Snapchat.

With growth stories like this being heralded as the goal, it’s easy to lose sight of the businesses that just make money every year, and will never have valuations like this. In fact, many denigrate these as “lifestyle” businesses or “hobbies”, because you’re selling out unless you Go Big or Go Home.

I think this is a mistake. If you can build a company that pays you well to do what you love, then that’s a pretty awesome outcome too. Bootstrapping a business to profitability is no mean feat.

The kind of rapid growth required to get you to a billion dollar valuation (particularly if your business model is unclear) requires outside money. And taking financial investment leads to certain inevitable outcomes. I think some founders mistake raising capital as an end in itself. So many press releases focus on money raised, rather than customers acquired or features released. Raising money is great, if that’s the path you want to be on. But you need to accept that financial investors have to see a return for their investment. And that means they need you to continue to grow, rapidly, and that you will have to (at some point) achieve liquidity for them by selling the business or taking to the public markets through an IPO. There is no option for you to take your foot off the gas and say “this is where I’d like to stop. the team’s big enough, we’ve worked hard enough, we’re going to enjoy the fruits of our labour now”.

If you want to spend a bit more time thinking about this, I recommend looking at Matt Haughey’s Webstock talk Lessons from a 40 Year Old, which talks about these choices in a great way.

If you decide you ARE going to be a billion dollar shark, then act like one.

You need to build for scale. Startups like to live by a “move fast and break things” mentality. There’s nothing wrong with moving quickly, but you need to understand the compromises you are making on the way through. We often talk about a sudden rapid growth in customers placing pressure on your product technically as a “great problem to have”, but as one founder said to me recently, “a great problem to have might be the last problem you have”. Keep an eye on your technical debt. Know where you’re cutting corners and know what you need to do. Have a plan for scaling as your business grows.

And scaling is not just about technical scaling. It’s also about “behaving” like a billion dollar company. First and foremost, keep a copy of everything you ever sign relating to the business. Everything. That means every cellphone contract, computer lease, bank overdraft application, domain hosting service or end user license agreement. (Yes, really. Even if you just click ‘accept’, save a copy or print it first.) Make sure everything is signed by both parties, and has a date on it. Services like Dropbox make this sort of record-keeping easy.

Make sure you sign things in the right name. Your accountant will give you the same advice – things that relate to the business need to be in the name of the company, not your personal name.

Always think about what you’re signing, how it might restrict you in the future, and for how long. There are a number of advisory services that will help with developing business plans or raising capital, but require the companies involved to sign contracts giving them exclusive rights for a period. Similarly, a simple confidentiality agreement signed early on with a company you later decide not to continue working with may prevent you from disclosing information to investors without their consent, even where your relationship with that company has come to an end.

Don’t let things continue indefinitely ‘on a handshake’, and don’t let key agreements expire and just keep going ‘as is’. If you have a key customer or supplier arrangement, it’s much better if there is a contract that documents it.

You don’t keep your accounts by sticking receipts in a shoebox. Don’t run the business side of your company in a crappy way either.

If you’re going to raise money, then the most important thing you need to focus on is your runway. An investor wants to know what you’re going to spend their money on. Lego walls and foosball tables are not the right answers.

But neither is “hiring a sales guy”. That’s not enough of an answer.

You have to understand how much money you’re burning and how long it is going to last.

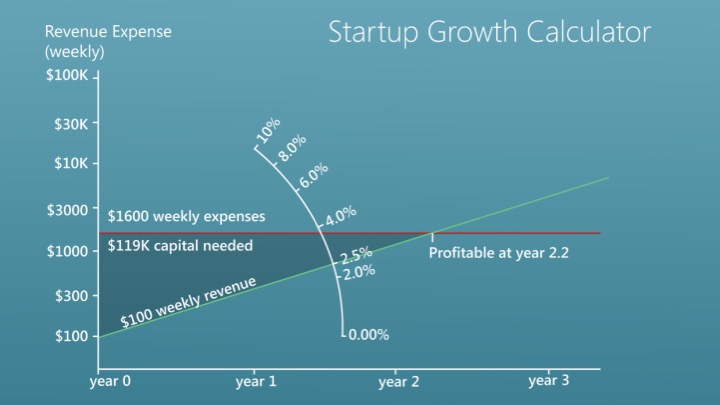

Here’s an online tool that can help from Y Combinator’s Trevor Blackwell, called the Startup Growth Calculator. Understanding your growth rate is critical. That’s the growth rate of revenue if you’re charging, and the growth rate of active users if you’re not.

This tool tells you when you will reach profitability and how much capital you need to reach that point. It’s flawed in some ways, it assumes a straight line on expenses when obviously your expenses will increase with your growth as you take on more AWS instances, or hire more staff, but it’s useful to play around with.

The other important thing to focus on is your cash. Understand how fast you’re burning it, when you’re going to run out, and if you’re on or off track.

All of this is to ensure that you raise ENOUGH money, so that you’re in a comfortable enough position to demonstrate growth before you have to do it again. And you will have to do it again. As a general rule of thumb, think about raising 18 months worth of runway. This gives you twelve months of working on the business, and six months to conclude your next funding round.

Once you’ve got a handle on your runway, make sure you understand the investors you’re planning to talk to. Think about the KIND of money you want. That is to say, do you want passive or active investors. Investors with particular skills, or access to particular networks, or history with businesses similar to yours. Do your homework on potential investors just as much as they will do their homework on you.

Don’t go into capital raising blind. There’s an absolute wealth of information online about what it’s like to negotiate with investors. A book I recommend regularly is Feld’s Venture Deals. How to be smarter than your lawyer and your venture capitalist. It walks through a standard Silicon Valley term sheet and it discusses each aspect of it from the point of view of the founder, and the investor, and the lawyer, so you can understand where each party comes from.

At a minimum, get to grips with the following:

The Type of Investment. Is it a convertible note (which is like a loan that can turn into shares), or is it equity? If it’s equity, will the investors be getting ordinary shares just like you, or will they be looking for a “preference”? If they’re preference shares, what kind of preference? What kind of special rights do their shares have?

The Valuation. One of the hardest things is actually pinning down the numbers. Are they talking to you about a pre-money or a post-money valuation (i.e. before or after the impact of their investment). What assumptions are they making? Sometimes they’ll be taking into account things like employee equity that may not even exist yet.

The Constraints on the Company. There’ll be a lot of talk about “standard protective provisions” or “standard investor rights”. You need to understand what these mean. Will the investors want to appoint directors to your board, will they want veto rights over key decisions, and if so, for how long? Will they want vetos over your next capital raising? How much information will they expect and how often will they want you to produce it. All of these can be things that will change the way you currently run your business.

The Warranties. Investors are going to want you to put your neck on the line about a range of things. And if those promises turn out to be untrue, they can claim for their loss. You need to understand what you’re warranting, whether its you personally or just the company, and you need to have the background to ensure what you’re saying is right (e.g. IP).

Basically, don’t try and raise money without a great lawyer in your corner.

Starting a business has never been easier. But what makes it easier for you, makes it easier for everyone, so you need to understand who your competition is. And chances are, that competition is not the other startup you know of building the (obviously) uglier, less featured version of your app.

Understanding your competitive environment means thinking laterally. Actually, it means thinking in ALL directions. What’s the risk that Google decides to offer your product for free, for example?

What if people are using a completely different tool to solve the problem you’ve identified? There’s no point in building a complex learning management system for people to teach skateboard tricks, if the best content is currently being shared on Youtube and that works fine for everyone. Don’t throw yourself a party if you google “skateboard tricks platform” and nothing shows up. Chances are you’ve thought about the question wrong.

Startup life is so hot right now. Founders are the new conquering heroes. People will congratulate you for “following your dream” and “doing what you love”, but you’ll also be expected to be “hustling” 24/7 or you’re doing it wrong. It’s a culture that rewards people who are “crushing it”, and doesn’t leave much room to admit when you’re struggling or stressed.

Long days, lack of sleep, the worry of being responsible for employees’ livelihoods and investors’ money. If you’re not careful, you’ll be the shark collapsed on the ocean floor.

Burnout is real. Investors and advisors are now starting to talk pretty openly about it. And you should too.

1. Recognise it in yourself and your team. Make a point of regularly checking in with your own habits, how many hours you’re working, how much time you’re spending with your family, when you last ate a salad instead of drinking another red bull. The occasional all-nighter might be a reality, but it shouldn’t be a habit.

2. Get help. Even before the stage where you might need a therapist. Surround yourself with a support network. In any city you’re in, you should be able to find a meetup of people working on similar things. We’re kicking off a new meetup for founders down at the Grid this month. It’s called Flounders Club. And the whole point is that founders flounder, and unless they’re able to share those struggles with others and get help with the challenges they’re facing, those challenges can feel insurmountable and isolating.

4. You don’t have to stop, but you do have to find a balance. Sleep. Exercise. Nutrition. Build THAT into your weekly plan.

5. Make it a top-down decision for your whole team. Don’t create a culture where people feel like they can’t ask for leave days, where they’ll be letting the team down if they leave the office before midnight. Don’t make every task in the workplan mission critical.

And one of the ways you can get help is to create a great governance structure around you. That’s about understanding who is running your company, and how they’re doing it.

The traditional legal company structure is designed to separate ownership from management. The owners (shareholders) are not typically the people running the show (directors). In startup companies, however, founders tend to fill both roles. It’s important for those of you who are directors to understand what that means legally.

As a director of a company you have a number of duties that you must comply with under the Companies Act. Most importantly you must act in good faith and in what you believe to be the company’s best interest. This is particularly important where a director is also a shareholder. As a director, your decisions need to put the company and not your own investment first.

If all of the founders are relatively inexperienced, you should think seriously about finding an independent director to join your board. Alternatively, you might decide to create an ‘advisory board’ of people experienced in your industry or sector, who are happy to provide advice and oversight on a regular basis.

The Institute of Directors has released this great toolkit online about forming an advisory board. It talks about how to approach and how, and gives you templates for work plans, meeting agendas and reporting dashboards.

But, how do you pay advisors in this situation?

It is very unusual for small companies to pay directors’ fees, other than perhaps a nominal amount for an independent director’s time and expenses. When it comes to advisors, some may have a standard hourly rate, and some may be more interested in a small amount of equity (both because they see upside in your company, and also because it is more interesting to them to have some skin in the game). The challenge for founders is to “value” the advice and input that these mentors might provide, without creating an onerous, long term commitment that is difficult to untangle if the relationship doesn’t work out.

For example, will they connect you with their network (and what does that even mean)? Actively promote you within their network? Or actively seek out funding for you? Do you expect them to meet with you quarterly? Monthly? Is their role just to test your assumptions by asking you lots of questions, or are you hoping they will give you proactive, strategic advice? All of these factors will contribute to how much you might pay them, or how much equity you might want to offer.

Ultimately it’s critical for founders to be honest about their strengths and weaknesses, and to identify people who can bring real skills to help the business grow. Don’t be afraid to interview potential directors and advisors extensively to make sure the chemistry and fit is right for your business, and as you would with any employee, trial the working relationship for a few months before you agree to make them shareholders.

Last, but definitely not least.

Think about who you’re working with. We all have a tendency to partner with, and to hire, people who are like us. Who have similar backgrounds and experience. Who have tinkered with computers since they were ten, and like the same console games and craft beer.

Here’s the problem. A bunch of people who think the same way will build a terrible business. Or at a minimum, they won’t build as successful a business as a team that doesn’t.

I can say the word “diversity” and many of you will tune out. You’ll argue that you’re more interested in skill than what someone looks like, or how old they are, or what their background is. You’re meritocratic. You’ll say that you’d be happy to cofound a business with a woman, or someone from a different ethnic background, but you just don’t know any with the right skills.

But you know what? The internet isn’t a place full of white dudes with beards. Unless you’re making a beard oil specifically for european beard hair, your CUSTOMERS are not even all white dudes with beards. And even if that was your product, chances are it’s their wives and girlfriends who are buying it anyway.

How are you going to build a business selling to a diverse customer base if you have noone on your team that represents that customer base?

More than that, innovation comes from diversity. This is basic “wisdom of crowds” stuff. If you all look at things the same way, you’re less likely to challenge your assumptions. You’ll overlook things. You won’t necessarily see flaws in your approach.

It’s also a better business decision. In the US analysis of more than 20,000 venture backed companies showed that successful start-ups have twice as many women in senior positions as unsuccessful companies. Tech companies with women in senior roles have been shown to use 40% less capital and be more likely to survive the transition from startup to established company. Those with the highest representation of women in their management teams have a 34% higher return on investment than those with few or no women.

People will still tell me, yeah but it’s hard. Sure it is. Founding a successful startup is hard too, and you’re not letting that put you off. Go looking. Go to the Girl Geek Dinner, and the Rails Girls weekends. Get around your local startup weekends and your developer meetups. Look for people who aren’t like you. Get help with writing your job ads. There’s all kinds of evidence that the language in job ads will affect who applies. Ask someone to take the name and gender off cvs before you look at them. See if that changes your approach at all.

Plus, putting it off isn’t going to make it easier. If you think, yeah, that makes sense, but it’s we need to move quickly so I’ll just hire these white dudes who are talented and available and I know who they are. I’ll work on diversity later. Later, it’s going to be harder to convince people to join and change an entrenched culture. Do it now.

Build a team that reflects the world, and your team will build a product that just might change it.

With grateful thanks to Jem Yoshioka who drew these extraordinary sharks.